Taking Pipeline LDAR to New Heights with Satellite and Aircraft Methane Data

By R. MATTSON, GHGSat, Quebec, Canada

(P&GJ) — In comparison to other oil and gas assets, pipelines present distinct challenges for operators seeking to build and manage effective leak detection and repair (LDAR) programs. Potential emission points are dispersed across infrastructure that stretches across potentially thousands of kilometers (km). Pipelines are often buried underground across remote, rugged or mountainous terrain with limited or no road access. The American Petroleum Institute (API) estimates that in the U.S. alone, there are more than 200,000 miles (mi) of liquid petroleum pipelines, connecting production sites, refineries and terminals. For natural gas, the network of gathering, transmission and distribution pipelines in the U.S. comprises 3-MM mi of infrastructure.

Notably, pipelines also demonstrate distinctive emissions trends. Some of the largest emissions typically come from specific areas, including gathering lines, compressor stations, pigging/collection stations or chemical injection sites. However, in addition to these more predictable emissions sources, there is also the risk of leaks from excavation damage, agriculture or vandalism—which are sudden and random, unlike emissions stemming from the more predictable equipment condition and wear.

For ground crews and repair teams, these factors add up to create a difficult environment for effective LDAR. Ground crews would need to patrol long, narrow corridors instead of compact facilities, dramatically raising inspection time and costs. Often, ground teams and drones cannot easily reach many sections of pipelines. Regular patrols may miss the sudden third-party damage events if they happen outside of routine inspections.

While these challenges are significant, they are not insurmountable. Pipeline LDAR is too critical to miss. According to Future Markets Insights, pipelines represent roughly 20%–35% of total oil and gas infrastructure investments or capital stock. Indeed, LDAR programs take on even more significance in today’s geopolitical environment, as the energy sector faces shifts in sustainability policy and a rising global emphasis on energy security—both of which are linked to the prevalence of methane emissions. Because methane has a warming effect roughly 80 times stronger than carbon dioxide (CO2) over a 20-yr period, reducing methane emissions is recognized as one of the most immediate and impactful ways to slow planetary warming.

However, cutting methane is not only environmentally responsible, but it also increases business competitiveness. Keeping methane in the pipeline, rather than the atmosphere, can boost yields for oil and gas producers. Accurate data on methane emissions also ensures operators can export to nations with stringent regulatory policies on emissions intensity. In addition, methane leaks can provide a first warning about asset health, prompting more efficient and optimized repair processes. This increased efficiency creates a competitive edge in today’s rapidly evolving energy sector.

But how to ensure that pipelines are not creating inefficiencies and potentially environmentally damaging emissions? With available technologies, including satellites, aerial technology and drones, operators can build an effective LDAR program to meet regulatory requirements while streamlining operations and reducing costs. The key to ensuring pipeline LDAR minimizes environmental risks while maximizing revenues is a multi-tiered monitoring approach, drawing on the strengths of each technology to detect and pinpoint emissions swiftly, confirm the source and ultimately address them. In particular, satellite and aircraft technology plays a foundational role in pipeline LDAR. Satellites can regularly cover the priority assets most likely to emit methane, detecting the majority of leaks to trigger follow-on investigations. The low detection threshold and relative ease of deployment of the aircraft enables targeted campaigns over larger stretches of pipeline, a much greater distance than ground-based sensors can cover. Building an effective playbook for effective LDAR requires first combining technologies for maximum effectiveness and leveraging the LDAR data across organizational processes.

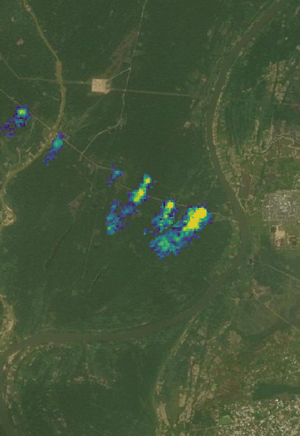

High-resolution satellites provide first alerts and regular monitoring for high-risk areas. The first weapon in an operator’s arsenal is the power of high-resolution satellites, which provide a first alert about methane by detecting methane emissions as small as 100 kilograms per hour (kg/hr)—the “super-emitter” threshold—and pinpointing them to a 25-meter (m) area. The advantage of satellites for monitoring pipelines lies in their spatial coverage: satellites are ideal for covering large or remote areas. From space, they still have a clear view of even the most challenging areas to access. High-resolution satellites can be targeted to observe areas most likely to emit methane—like compressor stations, pigging stations or chemical injection sites—at a regular cadence.

For example, the author’s company’s constellation of satellites, the largest in the market, monitors millions of sites annually and can revisit a given industrial site at a daily frequency. The robust coverage, combined with an operationally useful revisit time, allows operators to monitor pipeline infrastructure globally, at a fraction of the cost of Earth-bound methods, to receive automated alerts of plumes intersecting pipeline corridors. With this information in hand, operators can swiftly identify the majority of emissions and quickly prioritize pipeline segments for repair.

Aircraft zoom-in for targeted campaigns. After satellites quickly detect and prioritize methane hot spots, aerial technologies can zoom in for finer detail to localize the plumes within meters. Ideal for targeted campaigns and rapid response programs, aerial technologies have a lower detection threshold than satellites, enabling them to spot smaller emissions and pinpoint their source. The author’s company’s airborne technologya operates at an altitude of 3,000 m, for example, so it can be used to scan across pipeline sections, detecting emissions at thresholds as low as 5 kg/hr. While airborne technology is a powerful tool, they are more limited by operational costs and logistics, like fuel, crew or airspace permissions compared to satellites. However, the system’s high levels of accuracy make it particularly valuable for screening complex, or high-risk infrastructure, with minimal disruption to operations. Drones and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) can also be layered in at the airborne level, as a next step for targeted inspections after a satellite flag.

Ground-based technologies enable component-level repair decisions. Finally, ground-based methods, like optical gas imaging (OGI) cameras, handheld sniffers or fixed sensors provide the most precise localization ability, and enable component-level repair decisions. Handheld analyzers give immediate confirmation and quantification for repair prioritization. While walking the entire length of a pipeline is not typically feasible or realistic for operators, ground-based methods working in tandem with the larger spatial coverage of satellites and high precision of aircraft have an important role: a final verification and repair tool.

Integrating emissions data into strategic processes and operations. After this data is collected, the question becomes: how can it be used most effectively? Holistic LDAR programs are not just stand-alone repair triggers. When integrated with in-line inspection (ILI) and maintenance systems, satellite-enabled LDAR transforms emissions detection into a risk-based, data-driven workflow. This layered approach ensures that safety and environmental priorities are addressed together, while providing continuous feedback that improves planning, resource allocation and regulatory compliance.

Ultimately, the data from these various technologies should be integrated into full operational strategy, particularly with ILI systems and maintenance processes. ILI tools, satellites and aircraft are complementary: while ILI tools target wall thinning, cracks or dents to detect structural risks for future leaks, emissions-monitoring technologies identify any resulting tangible emissions. Integrating datasets from both tools into systematic maintenance planning helps operators see both risks and realized events. If a satellite repeatedly detects methane near a compressor station flagged by ILI as having anomalies, that area can be escalated for immediate excavation and repair. By layering emissions detections with ILI findings or other asset condition data, operators can prioritize limited maintenance budgets towards segments with high emissions probability and structural risks.

Satellite data can also be automatically integrated into a computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) as preliminary work orders, triaged with severity scores driven by factors like flux size, population sensitivity and ILI risk ratings, to develop repair timelines. After maintenance crews complete repairs, subsequent satellite passes can verify that emissions have ceased, closing the loop and providing evidence for regulatory reporting and performance tracking.

This playbook has been used at scale by multinational oil and gas operators globally, leveraging the power of satellite monitoring as part of an effective LDAR system to drive tangible economic and environmental benefits. Take one December 2024 mitigation as a case in point. In the Permian, satellitesb picked up an emission at 1,039 kg/hr, alerting the operator within hours, who was able to act, drawing on ground-based technologies to verify the leak. Follow-up satellite observations confirmed mitigation. If left unabated, the emission would have cost the operator $1.3 MM/yr, based on the 2024 average Henry Hub spot price.

In the face of the unique challenges posed by pipeline infrastructure, no single leak detection method can do the job alone. Satellites provide the wide-area visibility and frequent coverage needed to spot large or recurring leaks across thousands of km and areas most likely to emit, while aircraft can rapidly pinpoint problem areas for more specific campaigns. Then, ground-based inspections deliver the confirmation and repair work that ultimately stops emissions. In the long-term, operators can maximize LDAR data by integrating it into long-term maintenance and strategic processes. Taken together, this multi-tiered approach offers operators the most effective, efficient and scalable pathway to cutting methane from pipelines—turning a complex monitoring challenge into a manageable, results-driven strategy.

NOTE

a GHGSat’s airborne technology

b GHGSat satellites

About the Author

RYAN MATTSON is the Vice President, Oil & Gas at GHGSat. Prior to joining GHGSat, he spent more than 15 yrs at Halliburton in global positions across Central Asia, North America and Asia. Mattson is a graduate of the University of Alberta.