Reliability Study Examines Slow Crack Growth and Burial Design Impact on HDPE Pipelines

By THEYLOR ANDRES AMAYA VILLABON, JUAN SEBASTIAN VALDERRAMA, PAULA JULIANA GARZON, CARLOS EDUARDO RODRÍGUEZ and GUILLERMO EDUARDO AVILA ALVAREZ, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

(Editor’s note: This installment is the first in a two-part series. The second section will be published in the December issue).

(P&GJ) — High-density polyethylene (HDPE) pipelines constitute the backbone of contemporary distribution systems for fluids that are crucial for industrial, municipal and residential infrastructures.1 Their inherent flexibility, durability and resistance to corrosion have made HDPE pipelines a dominant choice, accounting for more than 95% of gas distribution infrastructure in North America and extensively used in distribution networks globally.1

This article delves into the behavior of HDPE, identifying two primary mechanisms of failure. Under conditions of excessive nominal stress, HDPE continues to deform slowly until it reaches a deformation large enough for the material to yield, swiftly followed by structural failure. This failure mechanism, preceded by creep or plastic deformation, manifests in what is known as the ductile state.

Conversely, locally intensified stress can initiate and gradually propagate a localized, slow crack growth (SCG). This SCG is characterized by the absence of plastic yield or localized deformation. This absence is indicative of the fracture process occurring in what is known as the brittle state. The working strength of each commercial grade of HDPE pipe material is determined by considering these two potential failure mechanisms.2

Focusing on the SCG mechanism, this article emphasizes a reliability analysis over time, guided by the life model of a polyethylene pipe as specified by ISO 9080:2012. Through a performance function informed by the evaluated time using a model, random variables and the Monte Carlo method, the article aims to delineate the reliability behavior of the pipeline.

The objective is to assess how the times at which the pipeline enters high and medium probability of failure levels due to SCG are affected by variables related to the geometric design of burial and soil class. These variables include pipeline diameter, depth of cover, bedding angle, trench width, soil class and compaction level.

While numerous investigations have explored the reliability of polyethylene pipelines over time,3 few have concentrated on the geometric burial variables and soil class, underscoring the importance of studying these aspects.

The typical lifespan expected for HDPE pipes is about 50 yrs. Nonetheless, the Plastics Pipe Institute notes that HDPE pipes used in municipal potable water or gas distribution systems can exceed a lifespan of 100 yrs. This impressive longevity stands out, especially when compared to traditional materials like copper, cast iron and galvanized steel, which generally last between 30 yrs and 50 yrs.

HDPE’s superior durability underlines the need to investigate if and how certain installation and environmental factors might affect its expected lifespan.2,3 In addition, the importance of specific burial conditions, such as precise bedding and embedment, might be overstated for pipes that are inherently stiff enough for basic installation.4

Such pipes can be simply laid on the trench bottom and backfilled with the excavated soil, provided the depth of cover is shallow, there are no live loads and the trench walls are stable. This suggests that under typical conditions, complex installation processes might not be necessary, raising questions about the conditions under which the integrity and functionality of HDPE pipes could be compromised.

In response, the study is designed to examine how varying geometric burial conditions and soil properties might influence the projected 50-yr lifespan of HDPE pipelines. The aim is to determine whether standard guidelines underestimate the impact of certain environmental and installation factors on the pipeline’s longevity and reliability.

Through detailed simulations and machine-learning analysis, the most crucial variables and how they specifically affect the risk of pipe failure associated with the SCG mechanism will be identified.

SCG model. ISO 9080:2012 outlines a mathematical model to predict the failure time of thermoplastic pipes (e.g., those made from HDPE) due to SCG. This failure mechanism is critical for the long-term performance of HDPE piping systems, where cracks propagate at a slow rate under sustained stress, potentially leading to failure.

Central to the standard is Eq. 1, which estimates the time to failure (tf) as a function of environmental and material parameters:

log10( tf ) = A + B/T + Clog10(σc)/T (1)

where,

A, B and C are material constants derived from empirical data T represents the absolute temperature in Kelvin σc is the hoop stress applied to the pipe, MPa.

The model provides a quantitative framework to assess the durability of polyethylene pipes under specific operating conditions, incorporating the effects of temperature and applied stress on the SCG process.

The constants A, B and C within the formula have been extensively studied and determined through various methods. For this study, the values adopted are those obtained from research on the structure and crack growth in gas pipes of medium-density and HDPE.5

The selected values A = –12.931, B = 5,904.042 and C = –996.957, are based on their findings for HDPE pipes. These constants reflect a comprehensive understanding of the material properties and crack growth behavior, providing a solid foundation for predicting the failure time of HDPE pipes due to SCG in this analysis.

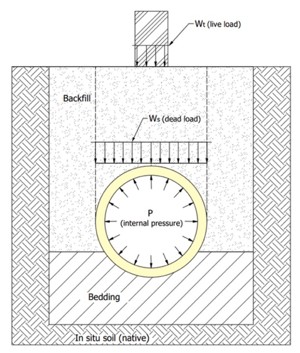

Hoop stress. Within the context of the SCG model for HDPE pipes, as outlined by ISO 9080:2012, hoop stress (σc) within the pipe walls is analyzed. This stress is a composite measurement that integrates the effects of internal and external loads on the pipe, as illustrated in FIG. 1, and is a parameter in the SCG model. Hoop stress is determined through the superposition of three principal stresses (Eq. 2):

σc = σh + σs + σg (2)

where,

σh denotes the hoop stress due to internal pressure p, MPa

σs is the additional stress from soil load (dead load) Ws, MPa

σg is the additional stress from traffic (live load), MPa.

For SCG failure mode analysis, long-term permanent loads are pertinent, negating the influence of stress contributions from live loads. For thin-walled pipes, the hoop stress attributable to internal pressure is explicitly described by Eq. 3:

σh = pmr/t (3)

where,

pm symbolizes the maximum operating pressure, MPa

r is the internal radius of the pipe, in.

t is the pipe wall thickness, mm.

To calculate the additional hoop stress due to soil load or traffic load, a modified version of Spangler’s formula is used.6 This method provides an estimate for the additional hoop stress at the bottom of the pipe due to a vertical load (Eq. 4):

σ = 6 KbWverEtr /Et3 + 24 Kzpmr3 + 0.732 Eʹ r3 (4)

Eq. 4 synthesizes the interaction between the pipe material, the load it bears and the properties of the supporting ground to accurately estimate the hoop stress σ, MPa. Wver represents the vertical load due to soil or surface loads such as traffic, MPa, and it encompasses the weight directly applied over the pipe, including the impact of vehicles or other pressures exerted from the surface above the installed pipeline; while E denotes the Young’s modulus of the pipe material.

Eʹ is the subgrade reaction modulus that quantifies the stiffness of the soil beneath the pipe, affecting how the ground supports the pipe and influences its deformation underload. The support factor Kz and the bending moment parameter Kb are influenced by the angle of bedding that supports the pipe. These parameters are necessary to determine the load distribution and the bending moments that the pipe will experience, directly impacting the hoop stress calculation.

Soil loads on pipelines—resulting from the weight of the soil—are computed by considering the soil prism’s weight directly above the pipe, in addition to shear forces transferred to this prism by adjacent soils. Spangler calculated the pressure transmitted to the pipe due to soil load, drawing on Marston’s load theory,6,7 as follows (Eq. 5):

Ws = CdγB2d (Dex/Bd) (5)

where,

Dex refers to the external diameter of the pipe, in.

γ is the unit weight of the backfill material, kg/m3

Bd is the width of the trench at the pipe’s crown, in.

Cd is the dimensionless load coefficient, a function of soil properties.

The calculation of the dimensionless load coefficient Cd is conducted via Eq. 6:

Cd = 1 − e −2 kμ Hback/Bd/ 2 kμ (6)

where,

k is the ratio between lateral unit pressure and vertical unit pressure

μ is the sliding friction coefficient between the trench sides and the backfill material

Hback is the height of the backfill material above the pipe crown, mm.

The values of k and μ can be determined using Eqs. 7 and 8:

k = tan2 (45∘ − ϕ/2) (7)

μ = tanϕ (8)

where,

ϕ represents the soil’s friction angle.

Reliability model. The reliability of HDPE piping systems against SCG can be quantitatively assessed using a performance function, denoted as Eq. 9:

G(xi) = t(xi)− tser (9)

where,

G(xi) ≤ 0 indicates failure, and a positive value signifies operational safety

t(xi) represents the time to failure predicted by ISO 9080 model for a given set of conditions, atser is the operational time of the pipe at the point of reliability analysis, a

the vector xi includes the random variables that account for uncertainties in the system.

The Monte Carlo simulation offers a robust method for estimating the probability of failure, that is, the likelihood that G(xi) ≤ 0. By randomly generating many scenarios based on the variability of input parameters (e.g., material properties, environmental conditions, applied stresses), this approach facilitates the computation of the distribution of G(xi).

Consequently, the failure probability can be determined as the proportion of simulations where G(xi) ≤ 0.4.2. This study delineates specific ranges for probabilities of failure (denoted as PoF in equations) due to SCG in HDPE pipelines, categorizing them into low, medium and high levels, as detailed in TABLE 1.8 These thresholds have been defined in accordance with the guidelines.

A transition to a medium probability of failure is identified when failure probabilities exceed 10−3 but remain below 10−2. This range highlights an area of increased concern, suggesting heightened vigilance though not yet at a critical level. Conversely, a high probability of failure is recognized for probabilities > 10−2, indicating a more urgent level of concern and the need for intervention to mitigate potential damages.

Variables for analysis. This section outlines the study variables alongside the random variables that will be incorporated into the previously discussed reliability model.

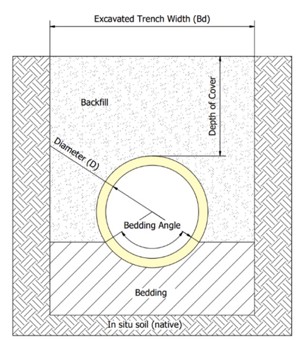

The study variables considered for analyzing the reliability of HDPE pipelines are illustrated in FIG. 2, depicting the geometric variables that will be assessed throughout the study, including the excavated trench width Bd, pipe diameter D, bedding angle and the depth of cover.

- Pipe diameter: The diameters under consideration are 3 in., 6 in., 10 in. and 12 in. These dimensions represent commercial sizes of HDPE pipes widely utilized in gas distribution networks.

- Depth of cover: Depths of 60 cm, 90 cm and 120 cm are analyzed, as these are commonly used in the burial of gas distribution pipelines.

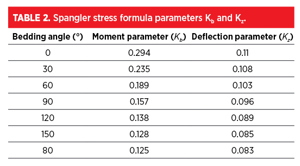

Bedding angle. All bedding angles reported by Spangler, including 0°, 30°, 60°, 90°, 120°, 150° and 180°, are analyzed and their impact on the Kz and Kb factors is detailed in TABLE 2. These angles significantly influence the hoop stress resulting from soil load, a critical factor for assessing the structural integrity of pipelines.6

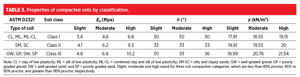

Soil classification and compaction. This article considers three backfill soil classes and their degree of compaction, represented as a percentage of standard proctor unit weight, as shown in TABLE 3. Both the soil class and the level of compaction significantly influence Ebʹ (modulus of elasticity of the backfill surrounding the pipe), ϕ (friction angle) and γ (bulk unit weight of the backfill material). These factors are necessary for understanding the interaction between the surrounding soil environment and the pipe, impacting its stress conditions and the probability of failure.

The values used in this article, derived from the soil properties defined in TABLE 3, are 30° for Class I soils, 33° for Class II soils and 30° to 36° for Class III soils, depending on the compaction level. These values were based on published standards and were applied consistently throughout the reliability analysis.9 The values for Ebʹ and γ were taken from Jeyapalan and Watkins (2004).10

Trench width to pipe diameter ratio (Bd/D). Ratios of 1.5, 3 and 5 are investigated to explore the significance of the trench width relative to the pipe diameter. This ratio is required for determining how external loads are distributed around the pipe and can affect the hoop stress experienced by the pipe.

Natural ground to backfill elasticity modulus ratio (Enʹ/Ebʹ). The article considers ratios of Enʹ/Ebʹ = 0.5 and 2, pivotal for calculating the combined modulus of elasticity of the soil reaction (Eʹ) in a buried pipeline environment. In conjunction with the trench width to Bd/D, these ratios aid in deriving the soil support combining factor, Sc, as outlined in TABLE 4. This factor is integral to Eq. 10, where Eʹ synthesizes the moduli of the native soil (Enʹ) and the backfill (Ebʹ).10

Eʹ = ScEbʹ (10)

This ratio and the corresponding calculation for Eʹ are necessary to evaluate how variations in stiffness between the immediate surroundings of the pipeline and the native soil properties affect the pipe’s behavior under load.

TEMPORAL RELIABILITY ASSESSMENT AND IDENTIFICATION OF CRITICAL FAILURE PROBABILITY THRESHOLDS

In the reliability analysis previously outlined, the stochastic nature of critical parameters is captured through six selected random variables, as delineated in TABLE 5.

The selection of these variables and their statistical properties are crucial, as they fundamentally influence the outcomes of the Monte Carlo simulations. The mean values and coefficients of variation (CV) for each variable were determined based on a combination of industry standards, manufacturer specifications and relevant literature.3

For instance, the modulus of elasticity (E) is set at a mean value of 750 MPa with a CV of 0.05, reflecting typical material properties for HDPE pipes, as reported in industry guidelines.11 The internal pressure (p) has a mean value of 60 psi and a CV of 0.05, based on standard operating pressures for gas distribution pipeline systems. The pipe-wall thickness is represented by the standard dimensional ratio (SDR), a dimensionless parameter defined as the ratio of the external diameter of the pipe to its wall thickness. The SDR for the pipes in this study is specified as SDR 11, with a CV of 0.06, reflecting dimensional tolerances provided by the pipe manufacturer and accounting for variability due to manufacturing processes.

The external pipe diameters (Dex) of 3 in., 6 in., 10 in. and 12 in. were selected to represent a range of pipeline sizes commonly used in the industry, with a minimal CV of 0.001 to reflect precise manufacturing controls and minimal dimensional variability.

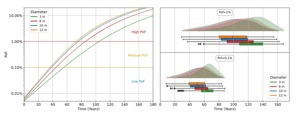

FIG. 3 displays a line graph showing the variation of the average probability of the failure with the time for pipeline diameters of 3 in., 6 in., 10 in. and 12 in., alongside combined box-and-whisker and half-violin plots illustrating the distribution around the threshold valves for medium- and high-probability of failure. The mean values of 60 cm, 90 cm and 120 cm with a CV of 0.1 account for typical installation depths and variability due to construction practices and soil settlement over time.

By integrating these well-defined stochastic parameters into the Monte Carlo simulations applied to the limit state function, it was found that the probability of failure for each set of study variables over an operational timeline spanned up to 200 yrs. This dynamic analysis not only yields year-by-year failure probabilities but also enables tracking of their progression over the pipeline’s service duration.

As a result, it generates a time-based profile of failure probabilities, providing the ability to identify trends and predict instances when a pipeline might reach designated thresholds of low, medium or high failure probabilities. From this perspective, the article identifies the years within the service life of the pipeline when the failure probability exceeds the thresholds defined in TABLE 1.

Deriving relative importances of study variables through machine learning. Following the identification of critical ages when pipelines exceed defined failure probability thresholds, specifically transitioning at 10–3 for medium and 10–2 for high levels of failure probability, an in-depth analysis was conducted using a random forest machine-learning algorithm. This analysis aimed to quantify the impact of various study variables on the age at which pipelines are projected to reach these specified probability of failure thresholds.

Random forest builds a multitude of decision trees during training and outputs the mean prediction of the individual trees. It quantifies the importance of variables based on the decrease in model accuracy when the values of a variable are permuted randomly across the dataset.

This shuffling breaks the direct link between the variable and the outcome, enabling the measurement of how much each variable contributes to model accuracy. The importance of each variable is computed by averaging the decrease in performance across all trees in the forest, which reflects the variable’s predictive strength.12

In this study, the random forest model was trained using the previously detailed study variables, with the response variable being the age at which pipelines are projected to enter defined probability of failure thresholds due to SCG. This approach is supported by literature that highlights the effectiveness of the random forest model in identifying critical risk factors and predicting infrastructure deterioration.

For instance, studies like that of emphasize the significance of factors such as pipe material and service life in the risk assessment of municipal pipeline networks, showcasing the ability of the algorithm to highlight critical risk factors.13,14

LITERATURE CITED

1 Walsh, T., “The plastic piping industry in North America,” Elsevier, Applied plastics engineering handbook, pp. 585–602, 2011

2 Plastics Pipe Institute, Handbook of polyethylene pipe, 2nd ed., 2008

3 Khelif, R., Chateauneuf, A., Chaoui, K., “Reliability-based assessment of polyethylene pipe creep lifetime,” 2007. Online: https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ijpvp.2007.08.006.

4 American Water Works Association, “PE Pipe – design and installation,” Manual of water supply practices—M55, 2nd ed., 2020

5 Trankner, T., Hedenqvist, M., Gedde, U.W., “Structure and crack growth in gas pipes of medium-density and high-density polyethylene,” Polymer Eng.Sci, 1996

6 American Water Works Association, et al., Spangler, M.G., “Pipeline crossings under railroads and highways,” 1964

7 Marston, A., “The theory of loads on pipe in ditches and tests of cement and clay drain tile and sewer pipe,” 1913

8 Joint Committee on Structural Safety (JCSS), “JCSS probabilistic model code,” 2001

9 Hartley, J.D., Duncan, J.M., “E and its variation with depth,” 1987

10 Jeyapalan, J.K., Watkins, R., “Modulus of soil reaction (E′) values for pipeline design,” 2004

11 Chevron Phillips Chemical, “Performance pipe,” online: https://www.cpchem.com/what-we-do /solutions/performance-pipe.

12 Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., Friedman, J.H., “The elements of statistical learning: Data mining, inference, and prediction,” 2nd ed. Springer, 2009

13 Hunag, C., Huang, D.L., Liu, Q., Zong, Z.L., Tang, A.P., “Application research on risk assessment of municipal pipeline network based on random forest machine learning algorithm,” 2023. Online: https://doi.org/10.3390/w15101964, 1964.

14 Tavakoli, R., Sharifara, A., Najafi, M., “Prediction of sewer pipe deterioration using random forest classification,” 2019

Additional References

ISO 9080:2012, “Plastics piping and ducting systems – determination of the long-term hydrostatic strength of thermoplastics materials in pipe form by extrapolation,” 2012. Online: https://www.iso.org/ standard/43860.html.

Trankner, T., Hedenqvist, M., Gedde, U.W., “Structure and crack growth in gas pipes of medium-density and high-density polyethylene,” Polymer Engineering and Science, 1996

Walsh, T., “The plastic piping industry in North America,” Elsevier, Applied plastics engineering handbook, 2011

Canada Energy Regulator, et al., Warman, D.J., Hart, J.D., Francini, R.B., “Development of a pipeline surface loading screening process & assessment of surface load dispersing methods,” 2009

Zha, S.X., Lan, H.Q., Huang, H., “Review on lifetime predictions of polyethylene pipes: limitations and trends,” 2022. Online: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijpvp.2022.104663.

Editor’s note: This article was previously published in the Journal of Pipeline Science and Engineering, Volume 5, Issue 2, June 2025, 100247. Creative Commons user license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/