Unpiggable Pipeline Integrity: CMI’s Aboveground AC Magnetometry Calculates EIR-Free and Corrosion Risk

By J. STUMME, Electromagnetic Pipeline Testing (EMPIT), Hamburg, Germany; and M. GLINKA, EMPIT, Berlin, Germany

(P&GJ) — Over the past century, thousands of kilometers (km) of pipeline networks for transporting gases and liquids have been laid worldwide. A typical protection against external corrosion is a combination of external coating and cathodic protection (CP) systems. However, as pipelines age, recurring safety inspections become increasingly important.

Today, the most reliable method to evaluate the condition—and thus the safety—of buried pipelines is via inline inspection (ILI) using “intelligent pigs” equipped with ultrasonic, magnetic flux leakage (MFL) or eddy-current sensors. These travel through the pipeline on the carrier medium. Based on the determined wall thickness at each point of the inspected pipeline sections, defect locations with enhanced corrosion risks can be identified.

Modern transmission pipelines are typically built with the necessary launch and receive stations for pigging. However, roughly 35%–40% of the existing U.S. pipeline networks are considered unpiggable.1 In addition, ILI technology only provides a snapshot of the material condition without assessing environmental influences at the location or distinguishing between active corrosion or passivated conditions.

Conventional over-the-line technology to assess pipeline coating integrity are direct current voltage gradient (DCVG) and close interval potential survey (CIPS). They are used to identify coating defects and assess CP effectiveness. However, it can only be assessed for large coating defects with a sufficient potential gradient. Additionally, it cannot be used to draw conclusions about active corrosion threats at defects where the CP system efficiency cannot be confirmed. According to several pipeline operators, for a severe number of assessed defects, where efficiency was not confirmed, no actively progressing corrosion is present due to a sufficient CP system, resulting in huge efforts and cost for unnecessary excavations.

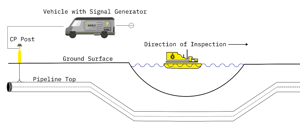

The current magnetometry inspection (CMI) methoda—developed by the author’s company—measures a self-applied magnetic field around buried pipelines from above ground. Deep-fusion artificial intelligence (AI)-based machine learning (ML) enables localization and advanced 3D mapping of any conductive pipelines and combines it with detection of coating defects and a direct local corrosion assessment. As the inspection along the pipeline is performed without any direct contact of the inspection tool with the pipe, it is suitable even for challenging geometries, complex structures and unpiggable pipelines (FIG. 1). Among other services, CMI determines whether steel at a coating defect is passivated—indicating effective CP—or whether there is an enhanced risk for active corrosion, resulting from insufficient CP. Thus, CMI precisely quantifies local CP effectiveness and enables direct conclusions about material condition at specific spots on the pipe.

The NEMEK research project. Building on CMI’s strong results, the German Technical and Scientific Association for Gas and Water (DVGW) launched the NEMEK research project to rethink corrosion protection for buried pipelines in general and give a reliable integrity assessment possibility for unpiggable pipelines. Germany’s largest transmission gas operators are partners in this project, which is also accompanied by the European Corrosion Committee (CEOCOR). In a two staged process, the applicability of the CMI methodology for locating coating defects, and the capabilities for assessing corrosion protection from above ground is validated.

First, a model pipeline, equipped with known artificial defects with various sizes, backfills and corrosion states was inspected using CMI in direct comparison to CIPS. In the second step, critical pipeline sections from project partners are assessed using CMI and then verified by excavation.

The CMI technology. The inspection setup is illustrated in FIG. 2. During CMI, a multi-frequency alternating current (AC) is applied to longitudinally conductive pipelines by a signal generator, resulting in a magnetic field around it. Because this inspection current is self-generated, the resulting field is precisely known and controllable. Intelligent optimization algorithms tailor the inspection current to the local geometric and electromagnetic characteristics of the pipeline and its surroundings.

The frequencies between 2 hertz (Hz) and 20,000 Hz penetrate soil layers with minimal attenuation and, by spanning a range of frequencies, enable clear separation of the pipeline signal from adjacent metallic or structural objects. Additionally, the method operates independently of external AC or DC interference, allowing the inspection of pipelines subject to strong stray currents that conventional techniques can only inspect with great difficulty.

The magnetic field is detected and evaluated from several air-, land- and water-based inspection units, with up to 20,000 measurement points per second with up to 70 sensors (FIG. 3). The different units allow seamless over-the-line pipeline inspections independent of surface conditions. For example, at water crossings—where integrity surveys are critical—autonomous drones or inspection boats (FIG. 4) can be used. In the future, offshore pipelines in depths up to 3,000 meters (m) could be surveyed by intelligent underwater vehicles (ROVs).

The spatially distributed arrangement of the sensors enables the magnetic field to be vectorially captured from above ground in all three spatial directions, as demonstrated in FIG. 5. The inspection unit maintains a direct digital link with the signal generator, which streams the current values—calculated from the magnetic field—back to the generator with millisecond latency at the exact pipeline coordinates. This feedback enables the signal generator to automatically optimize the signal-to-noise ratio on the pipe.

Next to the current on the pipeline, the measurement data allows the identification of the current flow direction and the distance of the buried pipeline from the inspection system above ground at any given moment. Combined with additional information from light detection and ranging (LiDAR), sonar or radar, and the system’s orientation, it makes CMI one of the most accurate method for absolute 3D pipeline positioning—even for complex structures and unpiggable pipelines.

Coating defects are detected and localized by a current leakage at a defect from the pipeline into the ground. Using deep-fusion AI-based algorithms further analyze the current flow in its complex form, allowing the resistive (ohmic) component to be separated from the capacitive component. Physically, the capacitance becomes measurable, reflecting whether a surface film has formed. This measurable presence of a surface layer strongly indicates a sufficiently effective CP system; a missing surface layer indicates the bare contact of steel and surrounding soil, signaling high risk for an active corrosion process (FIG. 6).

Moreover, by time-correlating the commanded and measured signals, full signal normalization becomes possible, allowing calculations of the IR-free potential (EIR-free), a method to assess the CP effectiveness, spread resistances and an identification of the presence of surface layers locally at defects for the first time with unmatched accuracy.

Thus, CMI combines the precise detection of coating defects with actionable insights on the local corrosion risk and CP effectiveness contactless from above ground for all pipelines, including unpiggable ones. Because the current is AC, inspections can be carried out without operation down-time or disrupting CP systems, which remain fully operational throughout the survey.

ARTIFICIAL TEST PIPELINE RESULTS

First, the performance of CMI was benchmarked with other conventional over-the-line surveys regarding EIR-free localization and determination. To do so, an artificial pipeline was inspected with multiple defect locations consisting of three test coupons each with sizes of 100 cm2, 10 cm2 and 1 cm², which could be selected individually for each location. Several inspection runs were performed with different configurations of defect arrangements. FIG. 7 shows the demonstration of the CMI on the artificial test pipeline.

FIG. 8 shows the localization of defects with a defect size of 1 cm² in a direct comparison between the aboveground inspection methods CMI (yellow) and CIPS (red). The results demonstrate that defects of 1 cm² are detected far more reliably by CMI with a possibility of detection (pod) of 100 % for CMI vs. 20 % for CIPS. Increasing CIPS’ sensitivity is possible; however, it requires a higher applied DC potential. Therefore, the inspection interferes with the CP system which can lead to further problems, including effects arising from soil-pipeline interactions, or even leading to delamination.

For heavily AC-influenced pipelines, shutting down or interfering with the CP system is not an option, so the CIPS cannot be employed. In addition to the higher defect localization sensitivity, using an AC source allows the CMI assessment to be conducted without interfering with regular operations. No downtime is required, and the CP system can be operated without any interference, making CMI also an option for heavily influenced pipelines from stray currents.

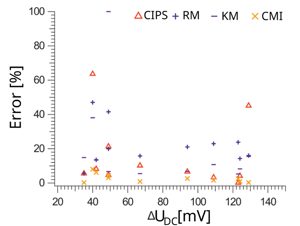

In addition to the localization of coating defects, the EIR-free was determined. According to German national standards body (DIN), European standard (EN) and International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 15589-1, the EIR-free is a sufficient parameter to confirm the effectiveness of a functioning CP system. FIG. 9 shows the error in the calculation of the EIR-free for various defect types and sizes across the different methods compared. The direct comparison shows that the CMI method allows a much more reliable determination of the EIR-free than the other compared methods [CIPS, reduction method (RM), correlation method (KM) and CMI], with an error consistently below 10%. Overall, CMI allows the calculation of the EIR-free with a higher sensitivity of at least a factor of five compared to the other methods.

However, if the calculated EIR-free misses the criteria of DIN EN ISO 15589-1, no further conclusions on the CP system and local corrosion risks can be drawn. Practical experiences show that only considering the EIR-free results leads to a significant number of unnecessary excavations.

Due to the applied bundle of several frequencies, CMI can further analyze corrosion risks by identifying effects originating from capacitive surface layers at coating defects. The capacitive surface layer can either inhibit the corrosion process or indicates sufficient CP with an elevated pH in the caustic region, which leads to precipitation of minerals, examplary displayed for a calcareous deposit in FIG. 10. The surface layer can thus, be used to confirm an effective CP system. In contrast to the EIR-free, it can be assessed for each coating defect, regardless of the size (down to 1 mm²) and resulting ground potential gradient. Thus, it delivers even more actionable insights into corrosion assessment than the determination of the EIR-free, minimizing costs and effort by avoiding unnecessary excavations.

Although both are aboveground measurement techniques, and thus, a suitable option for assessment of unpiggable pipelines, the direct comparison of the CIPS and CMI technologies shows the following:

- CMI provides more reliable insights for information-based decision-making, as detection sensitivity is much higher for smaller defects at the same inspection conditions. Independent of the bedding, all coating defects of a size of 1 cm2 were located correctly with CMI, while CIPS was able to identify 20%.

- CMI uses a self-applied AC, the pipeline operation—including the CP system—is not affected by the inspection. It also enables the inspection of influenced pipelines from stray currents.

- The IR-free potential values determined using CMI had a much smaller error of less than 10%, leaving CMI with a higher sensitivity of a factor of at least five compared to the other regarded methods.

- Next to the EIR-free, CMI provides information about the presence of a surface layer on the pipeline for all coating defects. That information leads to conclusions of the CP system efficiency locally at each coating defect, providing critical information on corrosion risks even where statements are not possible from EIR-free.

OPERATOR PIPELINE 1

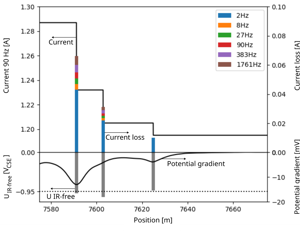

Situation. The surveyed pipeline partially traverses an airport perimeter and a nearby suburban neighborhood. FIG. 11 shows the current running in the pipeline at an exemplary frequency of 90 Hz as the black line. Additionally, the current loss is plotted at each defect as a colored bar stacked behind each other for the different frequencies applied. The resulting ground potential gradients (black line) and the calculated EIR-free (gray bars) are also displayed, indicating the relative size of the coating defect and the classification of defects according to the protection criteria of DIN EN ISO 15589-1 respectively. The black dotted line indicates an EIR-free of –0.95 V, with more negative values meeting the criteria for an effective CP protection.

At positions 7,593 m, 7,602 m and 7,624 m, insufficient coating leads to AC attenuation, resulting in an increased soil potential gradient. At positions 7,593 m and 7,602 m, the total loss differed for the different applied currents, as indicated by the stacked bars behind each other. This frequency-dependent behavior is typical for coating defects, on which a surface layer is present. The EIR-free was determined < –0.95 V for both defects, also meeting the criteria of an effective CP system.

However, at position 7,624 m, a respectively smaller defect, no frequency dependency could be observed as the current loss was same for all frequencies, indicated by the lowest frequency being the only visible block. It shows the absence of any surface layer and bare steel surface to ground contact. In addition, the EIR-free was determined as > –0.95 V. Therefore, criteria for a sufficient local CP system’s effectiveness according to DIN EN ISO 15589-1 are not met. Altogether, the coating defect was classified as a high corrosion risk hazard. A previously carried out ILI also indicated severe metal loss at the same relative pipeline location, supporting the results from the CMI.

Verification. The excavation of the defect, which was in the populated area as seen in FIG. 12, confirmed its exact position and existence as predicted by CMI. After excavation, active corrosion was identified, confirmed by corrosion byproducts and a slightly acidic pH at the steel surface. Additionally, the exposed and cleaned steel surface exhibited pronounced, localized metal loss consistent with the ILI data, as demonstrated in FIG. 13. These observations confirmed that the CP system was locally ineffective, as concluded from the CMI assessment.

Both (ILI and CMI) have successfully identified the significant integrity threat at the defect location. However, while ILI offers a static snapshot of the metal-loss, CMI adds the value of distinguishing between ongoing corrosion and already‐stabilized areas. This dynamic insight, combined with ILI’s metal‐loss measurements, enables targeted, timely mitigation and strengthened the overall risk‐informed asset management strategy.

OPERATOR PIPELINE 2

Situation. A segment of a bitumen coated steel pipeline for gas transport was inspected, and parts of the pipeline run alongside a solar park (FIG. 14). Several coating defects were also detected in that area, combined with CMI’s corrosion risk assessment. Five of these defects were selected for verification and excavated, from which only one was assessed as a high corrosion risk hazard (FIG. 15). Here, no formation of a surface layer could be observed, indicating insufficient CP system effectiveness.

Verification. For all five excavated coating defects, the presence of a coting defect, the defect location and the predicted state of corrosion were correct. At the defect with the high corrosion risk, active corrosion processes could be observed (FIG. 16). At all other locations, high pH values at the steel surface, as well as calcareous deposits confirmed a sufficiently working CP system.

The anomaly with active corrosion, a size of approximately 8 cm² and a maximum depth of 17% was not previously reported by an ILI carried out in 2023. It can be concluded that either the anomaly was overseen by ILI or that severe active corrosion happened in a short period with a critically high corrosion rate. However, CMI could again provide accurate and actionable insights due to a reliable corrosion risk assessment.

Takeaway. Results show that CMI has a significantly higher detection sensitivity especially for smaller defects than CIPS. In addition, the calculation of the EIR-free, which can be used to confirm CP effectiveness, is much more precise, with an error of < 10%. While CIPS can only identify and provide information on larger defects, CMI closes the gap by distinguishing between surface layer formation vs. high risk for active corrosion at the pipeline surface to soil interphase for each coating defect. Therefore, it provides an additional factor for evaluating the CP system's sufficiency for a safe pipeline operation.

Overall, CMI offers an over-the-line survey that not only complements but, in many respects, enhances and even presents an alternative conventional ILI for reliable integrity assessments:

- Actionable wall-state insight: While ILI delivers information wall loss along piggable lines, it cannot distinguish between stabilized (passivated) defects and actively corroding metal. In contrast to other over-the-line inspections, CMI fills that gap by directly analyzing the local CP effectiveness and corrosion risk. This allows operators to prioritize excavations and repairs based on active threats rather than only metal-loss magnitude.

- Integrated risk-informed asset management: By combining ILI’s static wall-loss data with CMI’s dynamic corrosion-state measurements, operators gain a holistic picture of pipeline condition. This integrated approach supports more targeted mitigation, extends inspection intervals where passivation is confirmed and concentrates resources on locations with true active corrosion—optimizing safety, lowering cost and reducing unnecessary excavations.

- Unpiggable pipeline integrity: Globally, roughly half of all buried pipelines—municipal distribution lines, water mains, older steel assets—are unpiggable and thus inaccessible to ILI. CMI’s aboveground method operates independent of installation or geometry with a high sensitivity for coating defect detection and corrosion assessment. Therefore, it uniquely enables full-network corrosion-risk surveys and integrity assessments in segments that would otherwise remain “blind spots” in any ILI-based program.

In summary, CMI is not merely an augmentation to ILI, it is a strategic enabler of comprehensive integrity management. Combining the methods provides actionable insights into combined metal-loss severity and ongoing corrosion activity. However, where ILI is not applicable, CMI extends full-network coverage to pipelines beyond the reach of any inline tool.

NOTE

a EMPIT’s current magnetometry inspection (CMI) method

LITERATURE CITED

1 A. Blackley, et al., “Pigging previously unpiggable pipelines,” PPIM Conference, February 2024, online: https://www.argusinnovates.com/public/download/files/244219

2 NEMEK, “Internal results provided from the Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Korrosionsschutz”

3 M. Buechler, et al., “Der Wirkungsnachweis des KKS: neue Erkenntnisse und Methoden, energie | wasser-praxis,” December 2024, online: https://energie-wasser-praxis.de/ausgabe-12-2024/

About The Authors

JAKOB STUMME is a Research Associate at EMPIT. He plays a pivot role in preparing and providing information on EMPIT’s over-the-line technology and capabilities—such as 3D mapping, detection of coating defects and corrosion assessment, as well as tailored inquiries for ensuring safe pipeline infrastructure using CMI. Serving as a key interface between development, data management and communication, Stumme ensures that complex technological insights are translated into actionable knowledge for internal teams and external partners.

MARK GLINKA is the Founder and Managing Director of EMPIT. He played a key role in the development and global introduction of CMI—a non-intrusive method to quantify corrosion, coating condition and 3D geometry across city gas networks, transmission lines, water crossings, horizontal directional drilling segments and geohazard corridors. Under his leadership, EMPIT has been recognized with Germany’s most prestigious innovation prize and has grown into the leading corrosion survey company in Europe. The company is now expanding its operations into the U.S. market.